Architecture

- Evolutionary Architecture

- Enterprise Integration Approaches

- Architecture Patterns

- Agile Software Architecture

- Software Architecture Documentation

- Bibliography

Ralph Johnson famously defined software architecture as “the important stuff (whatever that is).” The architect’s job is to understand and balance all of those important things (whatever they are).

Evolutionary Architecture

- the craft of software architecture manifests in the ability of architects to analyze business and domain requirements along with other important factors to find a solution that balances all concerns optimally.

- Unicyclist & Architect

- Visualize a unicyclist carrying boxes: dynamic because she continues to adjust to stay upright and equilibrium because she continues to maintain balance. In the software development ecosystem, each new innovation or practice may disrupt the status quo, forcing the establishment of a new equilibrium.

- Metaphorically, we keep tossing more boxes onto the unicyclist’s load, forcing her to reestablish balance.

- In many ways, architects resemble our hapless unicyclist, constantly both balancing and adapting to changing conditions.

- The engineering practices of Continuous Delivery represent such a tectonic shift in the equilibrium

- Change is inevitable

- Consequently, we should architect our systems knowing the technical landscape will change.

- Enterprise architects and other developers must learn to adapt. Part of the traditional reasoning behind making long-term plans was financial; software changes were expensive. However, modern engineering practices invalidate that premise by making change less expensive by automating formerly manual processes and other advances such as DevOps.

- Gradual degrade

- Even if the ecosystem doesn’t change, what about the gradual erosion of architectural characteristics that occurs? Architects design architectures, but then expose them to the messy real world of implementing things atop the architecture. How can architects protect the important parts they have defined?

- How to prevent?

- An unfortunate decay, often called bit rot, occurs in many organizations. Architects choose particular architectural patterns to handle the business requirements and “-ilities,” but those characteristics often accidentally degrade over time.

- Once they have defined the important architectural characteristics, how can architects protect those characteristics to ensure they don’t erode?

- For example, if an architect has designed an architecture for scalability, she doesn’t want that characteristic to degrade as the system evolves. Thus, evolvability is a meta-characteristic, an architectural wrapper that protects all the other architectural characteristics.

- a side effect of an evolutionary architecture is mechanisms to protect the important architecture characteristics. We call that continual architecture: building architectures that have no end state

- Incremental Change

- Incremental change describes two aspects of software architecture:

- how teams build software incrementally

- and how they deploy it.

- Example of incremental change at the architectural level: the original service can run alongside the new one as long as other services need it. Teams can migrate to new behavior at their leisure (or as need dictates), and the old version is automatically garbage collected.

- Making incremental change successful requires coordination of a handful of Continuous Delivery practices.

- Incremental change describes two aspects of software architecture:

- Guided Change

- Once architects have chosen important characteristics, they want to guide changes to the architecture to protect those characteristics.

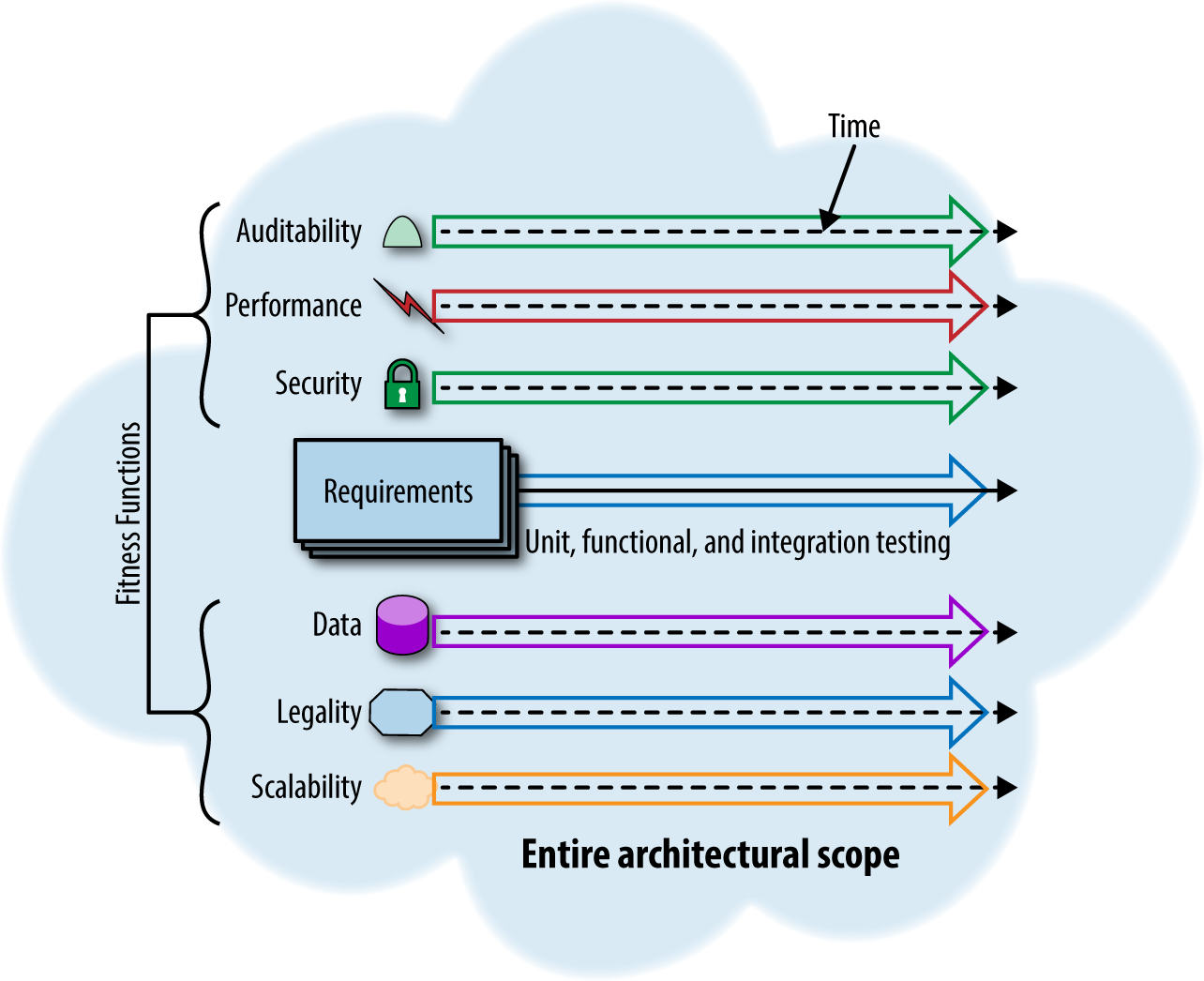

- For that purpose, we borrow a concept from evolutionary computing called fitness functions. A fitness function is an objective function used to summarize how close a prospective design solution is to achieving the set aims.

- as architecture evolves, we need mechanisms to evaluate how changes impact the important characteristics of the architecture and prevent degradation of those characteristics over time. The fitness function metaphor encompasses a variety of mechanisms to ensure architecture doesn’t change in undesirable ways, including metrics, tests, and other verification tools.

- When an architect identifies an architectural characteristic they want to protect as things evolve, they define one or more fitness functions to protect that feature.

- Architectural fitness functions allow decisions in the context of the organization’s needs and business functions, while making the basis for those decisions explicit and testable.

- an approach that balances the need for rapid change and the need for rigor around systems and architectural characteristics.

- Architectural Dimensions

- enlightened architects have increasingly viewed software architecture as multidimensional. Continuous Delivery expanded that view to encompass operations. However, software architects often focus primarily on technical architecture, but that is only one dimension of a software project. If architects want to create an architecture that can evolve, they must consider all parts of the system that change affects.

- To build evolvable software systems, architects must think beyond just the technical architecture.

- Examples of dimensions of architecture — the parts of architecture that fit together in often orthogonal ways. Some dimensions fit into what are often called architectural concerns (the list of “-ilities”), but dimensions are actually broader, encapsulating things traditionally outside the purview of technical architecture.

- To build an evolvable system, architects must think about how the system might evolve across all the important dimensions.

- Dimensions

- Technical: The implementation parts of the architecture: the frameworks, dependent libraries, and the implementation language(s).

- Data: Database schemas, table layouts, optimization planning, etc. The database administrator generally handles this type of architecture.

- Security: Defines security policies, guidelines, and specifies tools to help uncover deficiencies.

- Operational/System: Concerns how the architecture maps to existing physical and/or virtual infrastructure: servers, machine clusters, switches, cloud resources, and so on.

- Partitioning Techniques

- A variety of partitioning techniques exist for conceptually carving up architectures. For example,

- the 4 + 1 architecture View Model: focuses on different perspectives from different roles and was incorporated into the IEEE definition of software architecture, splits the ecosystem into logical, development, process, and physical views.

- Simon Brown’s C4 notation partitions concerns for aid in conceptual organization

- Conway’s Law

- Organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

- in a layered architecture where the team is separated by technical function (user interface, business logic, and so on), solving common problems that cut vertically across layers increases coordination overhead. People who have worked in startups and then have joined joined large multinational corporations have likely experienced the contrast between the nimble, adaptable culture of the former and the inflexible communication structures of the latter.

- Conway was effectively warning software architects to pay attention not only to the architecture and design of the software, but also the delegation, assignment, and coordination of the work between teams.

- Although each team may be good at their part of the design (e.g., building a screen, adding a back-end API or service, or developing a new storage mechanism), to release a new business capability or feature, all three teams must be involved in building the feature.

- it’s hard for someone to change something if the thing she wants to change is owned by someone else. Software architects should pay attention to how work is divided and delegated to align architectural goals with team structure.

- Many companies who build architectures such as microservices structure their teams around service boundaries rather than siloed technical architecture partitions (called the Inverse Conway Maneuver ).

- In microservices architecture, build cross-functional teams that matched the purview of the service: each service team consists of service owner, a few developers, a business analyst, a database administrator (DBA), a quality assurance (QA) person, and an operations person.

Enterprise Integration Approaches

There have historically been four approaches to integration: file transfer, sharing a database, leveraging services, and asynchronous messaging. One way to look at these approaches is how they affect coupling in your architecture. Broadly, there are three types of coupling:

- Spatial coupling (communication): Spatial coupling describes the requirement of a producer to know how to communicate with another and how to overcome error scenarios in the communication. A server side fault in an RPC operation, for example, is an example of spatial coupling.

- Temporal coupling (buffering): Temporal coupling describes the requirement of a producer to be aware of, and available for, a consumer to share data. A decoupled system uses buffering so that a message may be sent, even if the consumer isn’t available to receive it.

- Logical coupling (routing): Logical coupling describes the requirement of a producer to know how to connect with the consumer. One way to fix this is to introduce a central, shared location where both parties exchange data. Then, if a producer decides to move (change IP, put up a firewall, and so on) or decides to add extra steps before publishing messages, the client remains

Architecture Patterns

Domain Driven Design

Tutorial

- Part 1: Domain-Driven Design and MVC Architectures

- Part 2: Domain-Driven Design: Data Access Strategies

- Part 3: Domain-Driven Design: The Repository

- Part 4: Sample Application

Domain Model

- Responsible only represent the concepts of the business, information about business situations and business rules

- Named after the nouns in domain space

- Should have both data and behaviour (basic idea of object oriented design)

- well connected with other domain objects with relationship and structure

- Examples of behaviour - validations, calculations, business rules

- Only business logic - no persistence or presentation logic

- Completely persistance ignorant (Mithra domain model breaks this)

Value Objects

- 2 value objects are equal if all their fields are equal. Although all fields are equal, you don’t need to compare all fields if a subset is unique - for example currency codes for currency objects are enough to test equality

- Should be immutable

- A value object should always override .equals() & .hashCode() in Java

- ValueObject

- Diff between Value objects and Domain objects?

Data Transfer Object

- Simply contain for a set of aggregated data that needs to be transfered across process or network boundary

- holds only data - no business logic

- Needs to be serializable to work with remote interfaces

- Usually an assembler is used to transfer data between DTOs and Domain objects

Service Layer

- Service layer on top of ‘Behaviourally rich domain model’ is recommended

- Should be a thin layer

Anemic Domain Model (Anti-pattern)

- Objects which has only data but no business logic.

- All the business logic is implemented in a separate ‘Service Layer’ - Domain model is used only for data

- Incurs all the cost of domain model - No benefits

- Cost related to mapping to database

Martin Fowler - Service Layer, Model Layer Eric Evans - Application Layer, Domain Layer

Domain Specific Language (DSL)

- http://blog.jooq.org/2012/01/05/the-java-fluent-api-designer-crash-course/

- http://www.infoq.com/articles/internal-dsls-java

- http://weblogs.java.net/blog/carcassi/archive/2010/02/04/building-fluent-api-internal-dsl-java

Naked Objects Pattern

Agile Software Architecture

- Agile-centric or plan-centric development. Architecture before or refactoring later?

- (-) academic style of writing.

- attribute-driven design (ADD) method

- business architecture process and organization

- the Rationale Unified Process’s 4+1 Views

- Siemens’ 4 Views

- architectural separation of concerns

Software Architecture Documentation

Rationale Unified Process’s 4+1 Views

The 4+1 view model intends to describe an architecture using five concurrent views. Each of them addresses a specific set of concerns.

- Logical view denotes the partitions of the functional requirements onto the logical entities in an architecture. This view illustrates a design’s object model in an object-oriented design approach.

- Process view is used to represent some types of ASRs, such as concurrency and performance. This view can be described at several levels of abstraction, each of which addresses an individual issue.

- Development view illustrates the organization of the actual software modules in the software development environment. This view also represents internal properties, such as reusability, ease of development, testability, and commonality. It is usually made up of subsystems, which are organized in a hierarchy of layers. This view also supports allocation of requirements and work division, cost assessment, planning, progress monitoring, and reasoning about reuse, portability and security.

- Physical view represents the mapping of the architectural elements captured in the logical, process, and development views onto networks of computers. This view takes into consideration the NFRs (e.g., availability, reliability (fault tolerance), performance (throughput), and scalability).

- Scenarios are used to demonstrate that the elements of other views can work together seamlessly.

Bibliography

- Books

- Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture - Martin Fowler

- Agile Software Architecture

- Building Evolutionary Architecture - Rebecca Parsons, Neal Ford, Patrick Kua

- http://martinfowler.com/bliki/ValueObject.html

- http://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/dataTransferObject.html

- http://java.sun.com/blueprints/patterns/TransferObject.html