Distributed Computing

- Scalability

- Fault tolerance

- Design Techniques

- System Models

- CAP Theorem

- Consistency Models

- References

Scalability

- Size scalability: adding more nodes should make the system linearly faster; growing the dataset should not increase latency

- Geographic scalability: it should be possible to use multiple data centers to reduce the time it takes to respond to user queries, while dealing with cross-data center latency in some sensible manner.

- Administrative scalability: adding more nodes should not increase the administrative costs of the system (e.g. the administrators-to-machines ratio).

There are 2 aspects to look at in scalability

(i) Performance (or latency) Depending on the context, this may involve achieving one or more of the following:

- Short response time/low latency for a given piece of work

- High throughput (rate of processing work)

- Low utilization of computing resource(s)

(ii) Availability (and Fault Tolerance) Distributed systems can take a bunch of unreliable components, and build a reliable system on top of them.

Systems that have no redundancy can only be as available as their underlying components. Systems built with redundancy can be tolerant of partial failures and thus be more available.

Availability = uptime / (uptime + downtime)

For example,

* less than 4 days downtime per year = 99% availability

* less than 9 hours downtime per year = 99.9% availability

* less than 1 hour downtime per year = 99.99% availability

Availability is in some sense a much wider concept than uptime, since the availability of a service can also be affected by, say, a network outage or the company owning the service going out of business (which would be a factor which is not really relevant to fault tolerance but would still influence the availability of the system). But without knowing every single specific aspect of the system, the best we can do is design for fault tolerance.

Fault tolerance

- ability of a system to behave in a well-defined manner once faults occur.

-

define what faults you expect and then design a system or an algorithm that is tolerant of them.

Constraints

Distributed systems are constrained by two physical factors:

- the number of nodes (which increases with the required storage and computation capacity)

- the distance between nodes (information travels, at best, at the speed of light)

Working within those constraints:

- a) an increase in the number of independent nodes increases the probability of failure in a system (reducing availability and increasing administrative costs)

- b) an increase in the number of independent nodes may increase the need for communication between nodes (reducing performance as scale increases)

- c) an increase in geographic distance increases the minimum latency for communication between distant nodes (reducing performance for certain operations)

Beyond these tendencies - which are a result of the physical constraints - is the world of system design options.

Design Techniques

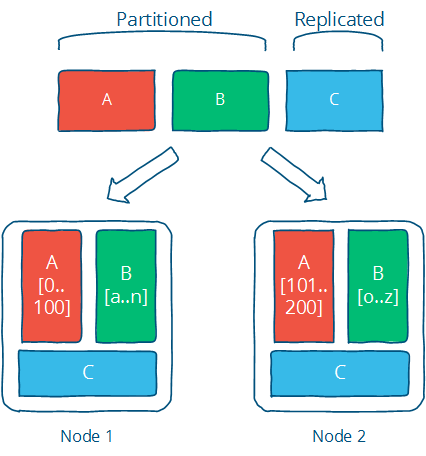

There are two basic techniques in which a data set is distributed between multiple nodes: partition and replication.

Partitioning

- Partitioning is dividing the dataset into smaller distinct independent sets; this is used to reduce the impact of dataset growth since each partition is a subset of the data.

- improves performance by limiting the amount of data to be examined and by locating related data in the same partition

- improves availability by allowing partitions to fail independently, increasing the number of nodes that need to fail before availability is sacrificed

- is also very much application-specific, so it is hard to say much about it without knowing the specifics.

- is mostly about defining your partitions based on what you think the primary access pattern will be, and dealing with the limitations that come from having independent partitions (e.g. inefficient access across partitions, different rate of growth etc.).

Replication

- Replication is making copies of the same data on multiple machines; this allows more servers to take part in the computation.

- It can also be copied or cached on different nodes to reduce the distance between the client and the server and for greater fault tolerance.

- improves performance by making additional computing power and bandwidth applicable to a new copy of the data

- improves availability by creating additional copies of the data, increasing the number of nodes that need to fail before availability is sacrificed

- is also the source of many of the problems, since there are now independent copies of the data that has to be kept in sync on multiple machines - this means ensuring that the replication follows a consistency model.

- Strong consistency allows you to program as-if the underlying data was not replicated. Weaker consistency models can provide lower latency and higher availability.

System Models

In a distributed system :

- each node executes a program concurrently

- knowledge is local: nodes have fast access only to their local state, and any information about global state is potentially out of date

- nodes can fail and recover from failure independently

- messages can be delayed or lost (independent of node failure; it is not easy to distinguish network failure and node failure)

- No shared memory or shared clock. Clocks may not synchronized across nodes (local timestamps do not correspond to the global real time order, which cannot be easily observed)

System Model is a set of assumptions about the environment and facilities on which a distributed system is implemented

System models vary in their assumptions about the environment and facilities. These assumptions include:

- what capabilities the nodes have and how they may fail

- how communication links operate and how they may fail and

- properties of the overall system, such as assumptions about time and order

A robust system model is one that makes the weakest assumptions: any algorithm written for such a system is very tolerant of different environments, since it makes very few and very weak assumptions.

On the other hand, we can create a system model that is easy to reason about by making strong assumptions. For example, assuming that nodes do not fail means that our algorithm does not need to handle node failures. However, such a system model is unrealistic and hence hard to apply into practice.

There are 3 main factors/properties affecting the Distributed computing

- Nodes

- Communication Links (between nodes)

- Time & Order

Nodes

Nodes serve as hosts for computation and storage. They have:

- the ability to execute a program

- the ability to store data into volatile memory (which can be lost upon failure) and into stable state (which can be read after a failure)

- a clock (which may or may not be assumed to be accurate)

Nodes execute deterministic algorithms: the local computation, the local state after the computation, and the messages sent are determined uniquely by the message received and local state when the message was received.

Communication Links

- Communication links connect individual nodes to each other, and allow messages to be sent in either direction.

- In general networks are considered to be unreliable and subject to message loss and delays. But some algorithms assume that the network is reliable (that messages are never lost and never delayed indefinitely). This may be a reasonable assumption for some real-world settings.

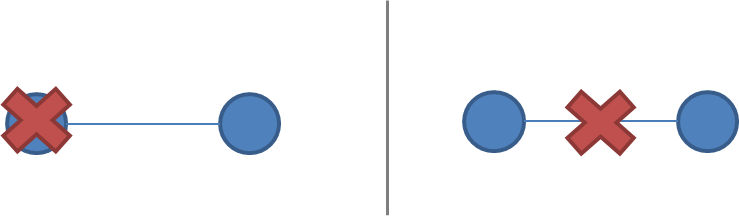

- A network partition occurs when the network fails while the nodes themselves remain operational. When this occurs, messages may be lost or delayed until the network partition is repaired. Partitioned nodes may be accessible by some clients, and so must be treated differently from crashed nodes. The diagram below illustrates a node failure vs. a network partition:

Timing/Order

- If nodes are at different distances from each other, then any messages sent from one node to the others will arrive at a different time and potentially in a different order at the other nodes.

Timing Assumptions / Timing System Models

- Synchronous System Model

- Processes execute in lock-step; there is a known upper bound on message transmission delay; each process has an accurate clock

- Asynchronous System Model

- No timing assumptions - e.g. processes execute at independent rates; there is no bound on message transmission delay; useful clocks do not exist

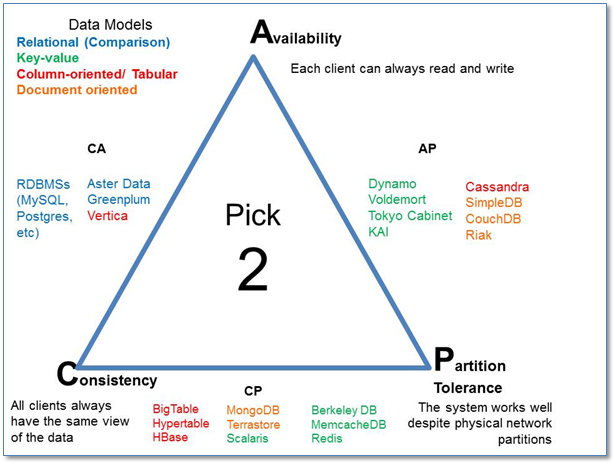

CAP Theorem

(Proposed by Eric Brewer in 2000, proved by Seth Gilbert and Nancy Lynch of MIT in 2002)

The theorem states that in any distributed system, only 2 of these 3 properties can be satisfied simultaneously:

- Consistency: all nodes see the same data at the same time.

- Availability: node failures do not prevent survivors from continuing to operate.

- Partition tolerance: the system continues to operate despite message loss due to network and/or node failure

|

|

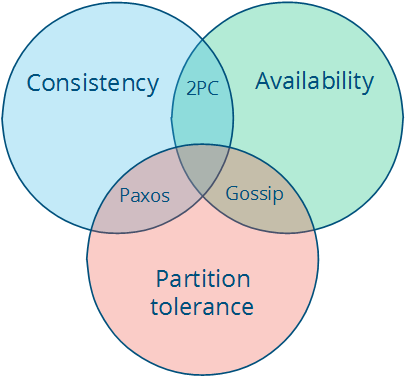

We get 3 different system types:

- CA (Consistency + Availability) * All relational DBs are CA. * When a partition occurs, the system blocks. * Examples include full strict quorum protocols, such as two-phase commit. * Strong consistency model; CANNOT tolerate any node failures * A CA system does not distinguish between node failures and network failures, and so the only safe thing is to stop accepting writes everywhere to avoid introducing divergence (or multiple copies). * CA systems are not partition-aware, and often use the two-phase commit algorithm and are common in traditional distributed relational DBs.

- CP (Consistency + Partition Tolerance)

* Say you have three nodes and one node loses its link with the other two. You can create a rule that a result will be returned only when a majority of nodes agree. So, despite having a partition, the system will return a consistent result. However, since the separated node won’t be able to reach consensus it won’t be available even though it’s up.

* Examples include majority quorum protocols in which minority partitions are unavailable such as Paxos.

* Strong consistency model; CAN tolerate node failures

* CP systems incorporate network partitions into their failure model and distinguish between a majority partition and a minority partition using an algorithm like Paxos, Raft or viewstamped replication. ( A primer on consensus)

* in a non-Byzantine failure model, a CP system can tolerate the failure of a minority

nnodes as long as majorityn+1stays up in a system with2n+1nodes. * A CP system prevents divergence (e.g. maintains single-copy consistency) by forcing asymmetric behavior on the two sides of the partition. It only keeps the majority partition around, and requires the minority partition to become unavailable (e.g. stop accepting writes), which retains a degree of availability (the majority partition) and still ensures single-copy consistency. - AP (Availability + Partition Tolerance) * Say you have two nodes and the link between the two is severed. Since both nodes are up, you can design the system to accept requests on each of the nodes, which will make the system available despite the network being partitioned. However, each node will issue its own results, so by providing high availability and partition tolerance you’ll compromise consistency. * The system is still available under partitioning, but some returned data may be inaccurate, e.g., DNS, caches, Master/Slave replication. * Needs a conflict resolution strategy. * Examples include protocols using conflict resolution, such as Dynamo.

In a distributed system, managing consistency(C), availability(A) and partition toleration(P) is important.

- Eric Brewer put forth the CAP theorem which states that in any distributed system we can choose only two of consistency, availability or partition tolerance.

- Consistency and availability are not really binary choices, unless you limit yourself to strong consistency. But strong consistency is just one consistency model: the one where you, by necessity, need to give up availability in order to prevent more than a single copy of the data from being active.

- Many NoSQL DBs try to provide options where the developer has choices where they can tune the DB as per their needs.

For example if you consider a distributed DB, there are essentially three variables r, w, n where

r= number of nodes that should respond to a read request before its considered successful.w= number of nodes that should respond to a write request before its considered successful.n= number of nodes where the data is replicated aka replication factor.

In a cluster with 5 nodes,

- we can tweak the

r,w,nvalues to make the system very consistent by settingr=5andw=5but now we have made the cluster susceptible to network partitions since any write will not be considered successful when any node is not responding. - We can make the same cluster highly available for writes or reads by setting

r=1andw=1but now consistency can be compromised since some nodes may not have the latest copy of the data.

Consistency Models

Consistency Model is a contract between programmer and system, wherein the system guarantees that if the programmer follows some specific rules, the results of operations on the data store will be predictable

There are 2 types of consistency models:

- Strong consistency model:

- guarantee that the apparent order and visibility of updates is equivalent to a non-replicated system

- Strong consistency models allow a programmer to replace a single server with a cluster of distributed nodes and not run into any problems

- Weak consistency model: do not make such guarantees

Below is not an exhaustive list

Strong consistency models

(capable of maintaining a single copy)

- Linearizable consistency

- Sequential consistency

Weak consistency models

(not strong)

- Client-centric consistency models

- Causal consistency: strongest model available

- Eventual consistency models

- Says that if you stop changing values, then after some undefined amount of time all replicas will agree on the same value. It is implied that before that time results between replicas are inconsistent in some undefined manner.

- how long is “eventually”? It would be useful to have a strict lower bound, or at least some idea of how long it typically takes for the system to converge to the same value.

- how do the replicas agree on a value? A system that always returns “42” is eventually consistent: all replicas agree on the same value. It just doesn’t converge to a useful value since it just keeps returning the same fixed value. Instead, we’d like to have a better idea of the method. For example, one way to decide is to have the value with the largest timestamp always win.

- So when vendors say “eventual consistency”, what they mean is some more precise term, such as “eventually last-writer-wins, and read-the-latest-observed-value in the meantime” consistency. The “how?” matters, because a bad method can lead to writes being lost - for example, if the clock on one node is set incorrectly and timestamps are used.