Java Concurrency

- Basics Concepts

- Locks

- Sharing Objects

- Publishing and Escaping

- Concurrency Problems

- Concurrency Limitations

- Executors Framework

- Concurrent Data Structures

- Synchronizers

- Java Memory Model

- Concurrency Programming Models

- Concurrency Frameworks

- FAQs

- Bibliography

Basics Concepts

- Thread

- Each thread has its own stack and local variable.

- Threads share the memory address space of the owning process; due to this, all threads have access to the same variables and allocate objects from same heap.

- Definitions

- Parallel processing - refers to two or more threads running simultaneously, on different cores (processors), in the same computer. It is essentially a hardware term.

- Concurrent processing - refers to two or more threads running asynchronously, on one or more cores, usually in the same computer. It is essentially a software term.

- Distributed processing - refers to two or more processes running asynchronously on one or more JVMs or boxes.

Threading Models

- Pre-emptive multi-threading

- OS determines when a context switch should occur

- System may make context switch at an inappropriate time

- This model is widely used nowadays

- Co-operative multi-threading

- The threads themselves determine relinquish control once they are at a stopping point.

- Can create problems if a thread is waiting for a resource to become available.

Thread Types

- Green thread

- Green threads emulate multithreaded environments without relying on any native OS capabilities. They run code in user space that manages and schedules threads;

- Scheduled by JVM rather underlying OS

- Sun wrote green threads to enable Java to work in environments that do not have native thread support.

- Uses cooperative multitasking - dangerous

- Native thread

- Uses underlying OS native threads

- Can be scheduled across cores in multi-core or multiprocessor systems

- Performs better than green threads even in single-core

Atomicity

Compound Action Anti-Patterns

Check-then-act

1 2 | |

Solution: synchronize or use concurrent methods like ConcurrentHashMap.putIfAbsent()

Read-modify-write

1

| |

Solution: synchronize or use atomic objects AtomicInteger.getAndSet()

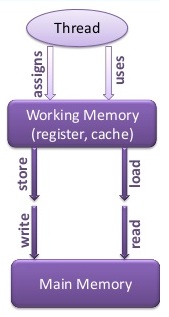

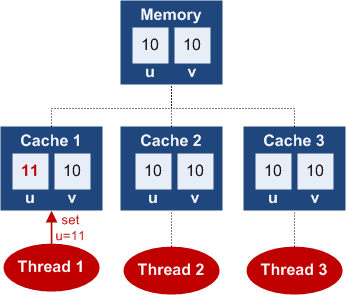

Visibility

Changes made by one thread may not be visible to other threads since the data could be residing in local working memory of a thread instead of main memory. In order to make it visible, Memory Barrier is needed. “Memory Barrier” means copying data from local working memory to main memory.

A change made by one thread is guaranteed to be visible to another thread only if the writing thread crosses the memory barrier and then the reading thread crosses the memory barrier. synchronized and volatile keywords force that the changes are globally visible on a timely basis; these help cross the memory barrier.

Synchronization

Synchronization allows you to control program flow and access to shared data for concurrently executing threads.

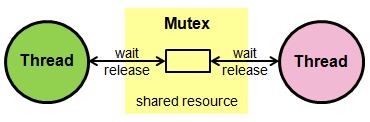

The four synchronization models are mutex locks, read/write locks, condition variables, and semaphores.

- 1) Mutex locks

- allow only one thread at a time to execute a specific section of code, or to access specific data.

- Each Java class and object has their own mutex locks. Each thread has it’s own separate call stack.

- 2) Read/write locks

- permit concurrent reads and exclusive writes to a protected shared resource. To modify a resource, a thread must first acquire the exclusive write lock. An exclusive write lock is not permitted until all read locks have been released. e.g.,

ReadWriteLock

- permit concurrent reads and exclusive writes to a protected shared resource. To modify a resource, a thread must first acquire the exclusive write lock. An exclusive write lock is not permitted until all read locks have been released. e.g.,

- 3) Condition variables

- block threads until a particular condition is true.e.g.,

java.util.concurrent.locks.Condition

- block threads until a particular condition is true.e.g.,

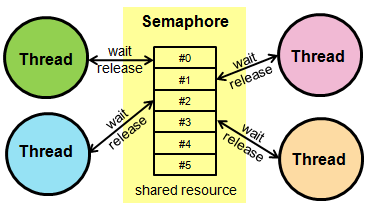

- 4) Counting semaphores

- typically coordinate access to resources. The count is the limit on how many threads can have access to a semaphore. When the count is reached, the semaphore blocks. e.g.,

java.util.concurrent.Semaphore

- typically coordinate access to resources. The count is the limit on how many threads can have access to a semaphore. When the count is reached, the semaphore blocks. e.g.,

Locks

Intrinsic Lock (synchronized keyword)

What should be used as a monitor?

- The field being protected. e.g.,

1 2 | |

- an explicit private lock e.g.,

1 2 | |

thisobject

1

| |

- Class-level lock

1

| |

What should not be used as a monitor?

- DO NOT synchronize on objects that can be re-used. Examples below: (For more information: Securecoding.cert.org - Do not synchronize on objects that may be reused)

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

- DO NOT synchronize on Lock objects.

1 2 | |

Limitations

- Single monitor per object

- Not possible to interrupt thread waiting for lock

- Not possible to time-out when waiting for a lock

- Acquiring multiple locks is complex.

Extrinsic Lock

Lock Interface

- implementations provide more extensive locking operations than cannot be obtained using

synchronizedmethods and statements. - Commonly, a lock provides exclusive access to a shared resource: only one thread at a time can acquire the lock and all access to the shared resource requires that the lock be acquired first. However, some locks may allow concurrent access to a shared resource, such as the read lock of a ReadWriteLock.

- offers more flexible lock acquiring and releasing. For example, some algorithms for traversing concurrently accessed data structures require the use of “hand-over-hand” or “chain locking”: you acquire the lock of node A, then node B, then release A and acquire C, then release B and acquire D and so on. Implementations of the Lock interface enable the use of such techniques by allowing a lock to be acquired and released in different scopes, and allowing multiple locks to be acquired and released in any order.

- Lock implementations provide additional functionality over the use of synchronized methods and statements by providing a non-blocking attempt to acquire a lock (

tryLock()), an attempt to acquire the lock that can be interrupted (lockInterruptibly(), and an attempt to acquire the lock that can timeout (tryLock(long, TimeUnit)). - Never use a Lock object as a monitor in a synchronized block

- Common idiom to follow

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Re-entrant locks/Recursive locking

Once a thread acquires the lock of an object, it can call other synchronized methods on that object without having to wait to acquire the lock again. Otherwise the method call would get into deadlock.

Condition

instead of spin wait (sleep until a flag is true) which is inefficient, use Condition. Even better is to use coordination classes like CountDownLatch or CyclicBarrier which is concise and better than Condition.

Sharing Objects

- “synchronized” guarantess 2 things

- ensures atomicity or demarcates ‘critical section’

- memory visibility - ensures other threads see the state change from a given thread

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

Possible outcomes

- prints zero and exists

- prints nothing and never ends

Reason

- changes made by main thread are not visitible to ReaderThread

- Stale values are visible

- changes made by main thread were visible to ReaderThread in a different order

Re-ordering

- Processor: could rearrange the execution order of machine instructions.

- Compiler: could optimize by rearranging the order of the statements.

- Memory: could rearrange the order in which the writes are committed to the memory cells.

- http://gee.cs.oswego.edu/dl/cpj/jmm.html

- http://www.cs.umd.edu/~pugh/java/memoryModel/DoubleCheckedLocking.html

Note: Always run server apps with “-server” JVM setting to catch re-ordering related bugs in development stage instead of prod.

Non-atomic 64-bit operations - JMM requires the read and write operations to be atomic, except ‘long’ and ‘double’ variables unless it is declared ‘volatile’. JVM is permitted to treat 64-bit read/write as two separate 32-bit operations.

Volatile Variables

In modern processors a lot goes on to try and optimise memory and throughput such as caching. This is where regularly accessed variables are kept in a small amount of memory close to a specific processor to increase processing speed; it reduces the time the processor has to go to disk to get information (which can be very slow). However, in a multithreaded environment this can be very dangerous as it means that two threads could see a different version of a variable if it has been updated in cache and not written back to memory; processor A may think int i=2 whereas processor B thinks int i=4. This is where volatile comes in. It tells Java that this variable could be accessed by multiple threads and therefore should not be cached, this guarantees the value is correct when accessing. It also stops the compiler from trying to optimise the code by reordering it.

In Java, volatile keyword does 3 things:

- prevents re-ordering of statements by processor/compiler/memory

- forces to read the values from memory instead of cache.

- guarantees atomicity in 64-bit data type assignments.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Volatile Arrays

Declaring an array volatile does not give volatile access to its fields! In other words:

- it is unsafe to call

arr[x] = yon an array (even if declared volatile) in one thread and then expectarr[x]to returnyfrom another thread; - on the other hand, it is safe to call

arr = new int[](or whatever) and expect another thread to then read the new array as that referenced byarr: this is what is meant by declaring the array reference volatile.

Solution 1: use AtomicIntegerArray or AtomicLongArray

The AtomicIntegerArray class implements an int array whose individual fields can be accessed with volatile semantics, via the class’s get() and set() methods. Calling arr.set(x, y) from one thread will then guarantee that another thread calling arr.get(x) will read the value y (until another value is read to position x).

Solution 2: re-write the array reference after each field write

This is slightly kludgy and slightly inefficient (since what would be one write now involves two writes) but is theoretically correct. After setting an element of the array, we re-set the array reference to be itself.

1 2 3 4 | |

More info:

Pros of volatile

- weaker form of synchronization

- notices JIT compiler and runtime that “re-ordering” SHOULD NOT happen.

- It warns the compiler that the variable may change behind the back of a thread and that each access, read or write, to this variable should bypass cache and go all the way to the memory.

- don’t rely too much on volatile for visibility

Limitations of volatile

- Synchronization guarantees both atomicity and visibility. Volatile guarantees only visibility

- Making all variables volatile will result in poor performance since every access to cross the memory barrier

Publishing and Escaping

- Publishing - making an object available to code outside of current scope. 2 ways of publishing - returning objects and passing it as parameter to another method.

- Escaping - An object published when it should not have been. e.g., partially constructed (Object reference visible to another thread does not necessarily mean that the state of the object is visible.)

Things to avoid

- Do not publish state via ‘public static’ fields. Solution: Use encapsulation

- Do not allow internal mutable state to escape

- (a) e.g.,

public String[] foo();<— Caller can modify the array. Solution: Use defensive copy. - (b) e.g.,

public void foo(Set<Car> car){}<— calling a method passing the reference. ‘foo’ can potentially modify ‘Car’ object. Solution: Use defensive copy. - (c) sub-classes can violate by overriding methods. Solution: Use final methods.

- (a) e.g.,

- Do not allow ‘this’ reference to escape via inner classes Solution: Use factory methods

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

- Don’t start threads from within constructors - A special case of the problem above is starting a thread from within a constructor, because often when an object owns a thread, either that thread is an inner class or we pass the this reference to its constructor (or the class itself extends the Thread class). If an object is going to own a thread, it is best if the object provides a start() method, just like Thread does, and starts the thread from the start() method instead of from the constructor. While this does expose some implementation details (such as the possible existence of an owned thread) of the class via the interface, which is often not desirable, in this case the risks of starting the thread from the constructor outweigh the benefit of implementation hiding.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

Thread Confinement

Do not share anything outside of the scope or at least outside of the thread.

- Adhoc - manually ensuring the object does not escape to more than a thread.

- Stack confinement - make it a local variable.

- ThreadLocal confinement - ensures each thread has its own copy of the object.

Data Sharing Options

- DO NOT share anything out of current scope

- DO NOT share anything out of current thread

- Share only immutable data

- Share mutable data - make vars volatile (thread safety not guaranteed)

- Share mutable data - make vars atomic

- Share mutable data - protect data using lock (intrinsic-lock synchronized or extrinsic-lock)

Immutability

- Immutable objects

- are inherently thread-safe since the state cannot be changed.

- Initialization Safety - JMM guarantees that immutables are published safely - meaning when the reference to an immutable is published, it is guaranteed that - the object is fully constructed

- Immutables offer additional performance advantage such as reduced need for locking or defensive copies.

An object is immutable if and only if

- its state cannot be modified after construction

- all its fields are final (not necessarily)

- it is properly constructed (‘this’ does not escape during its construction)

Safe Publication

To publish an object safely, both the reference to the object and the state of the object must be visible to the other thread at the same time.

A properly constructed object can be safely published by:

- Initializing an object reference from static initializer (executed by JVM at class initialization)

- storing the reference in a ‘volatile’ field or ‘AtomicReference’

- storing the reference in a ‘final’ field of a properly constructed object

- storing the reference in a field guarded by a lock

Concurrency Problems

1) Race condition

- If 2 threads compete to use the same resource of data, we have a race condition

- A race condition doesn’t just happen when 2 threads modify data. It can happen even when one is changing data while the other is trying to read it.

- Race conditions can render a program’s behavior unpredictable, produce incorrect execution, and yield incorrect results.

Hazards of Liveness - deadlocks, livelocks, starvation and missed signals

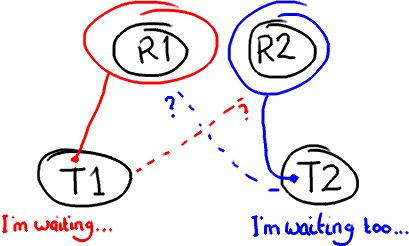

2) Deadlock

Type 1: Lock-Ordering Deadlock

- Thread 1 holds lock A and waits for lock B. Thread 2 holds lock B and waits for lock A. (e.g., Dining philosopher’s problem) This is a cyclic locking dependency, otherwise called ‘deadly embrace’.

- DBs handle deadlock by victimizing one of the threads. JVMs don’t have that feature.

Dynamic lock-ordering deadlocks

below code deadlocks if 2 threads pass in the same objects in different order

1 2 3 | |

To prevent this, use some kind of unique values like System.identityHashCode() to define the order of locking. If the objects being locked has unique, immutable and compareable-keys, then inducing locking order is even easier.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Open Calls

Calling an alien method with no locks held is known as ‘open-calls’. Invoking alien method with locks held is asking for liveness trouble because the alien method might acquire other locks leading to lock-order deadlocks. Here is an innocent looking example: Thread 1 calls setLocation() locking Taxi and waiting for lock on Dispatcher. Thread 2 calls getStatus() locking dispatcher and waiting for lock on Taxi.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

Type 2: Thread-starvation deadlocks

- Task that submits a task and waits for its result in a single-threaded executor

- Bounded pools and inter-dependent tasks don’t mix well.

How to avoid deadlocks?

- Avoid acquiring multiple locks. If not, establish lock-ordering protocol

- Use open-calls while invoking alien methods

- Avoid mixing bounded pools and inter-dependent tasks

- Attempt timed-locks (lock-wait timeouts)

How to detect deadlocks?

- Via JConsole (detect deadlocks tab) or VisualVM

- Using

ThreadMXBean.findDeadlockedThreads() - Get thread dump via the following methods and analyse

- native

kill -3command - In pre-Java 8,

jstack <pid> > file.log - From Java 8,

jcmd <pid> > file.log- for enhanced diagnostics and reduced performance overhead. -XX:+UnlockDiagnosticVMOptions -XX:+LogVMOutput -XX:LogFile=jvm.log- this JVM option will output all JVM logging into jvm.log file which will include thread dump as well.

- native

3) Starvation

occurs when a thread is perpetually denied access to a resource it needs to make progress; most commonly the CPU cycles. In Java it typically happens due to inappropriate use of thread priorities.

4) Livelocks

is a form of liveness failure in which a thread, while not blocked, still cannot make progress because it keeps retrying an operation that will always fail. It often occurs in transactional messaging applications, where the messaging infrastructure rolls back a transaction if a message cannot be processed successfully, and puts it back at the head of the queue. (This is often also called ‘poison message’ problem).

5) Missed Signals

…

6) Fairness

…

Concurrency Limitations

Concurrency/Parallelism does not necessarily make a program run faster; it may even make it slower. Here’s why:

- Overhead is work that a sequential program does not need to do. Creating, initializing, and destroying threads adds overhead, and may result in a slower program. Using thread pools may reduce the overhead somewhat.

- Non-parallelizable computation: Some things can only be done sequentially.

- Amdahl’s law

- states that the speedup of a program using multiple processors in parallel computing is limited by the time needed for the sequential fraction of the program

- in other words, it states that if 1/5 of a computation is inherently sequential, then the computation can be speeded up by at most a factor of S. For example, if 1/5 of a computation must be done sequentially and 4/5 can be done in parallel, then (assuming unlimited parallelism with zero additional overhead) the 4/5 can be done “instantaneously”, the 1/5 is not speeded up at all, and the program can execute 5 times faster.

- Idle processors: Unless all processors get exactly the same amount of work, some will be idle. Threads may need to wait for a lock, processes may need to wait for a message.

- Amdahl’s law

- Contention for resources: Shared state requires synchronization, which is expensive.

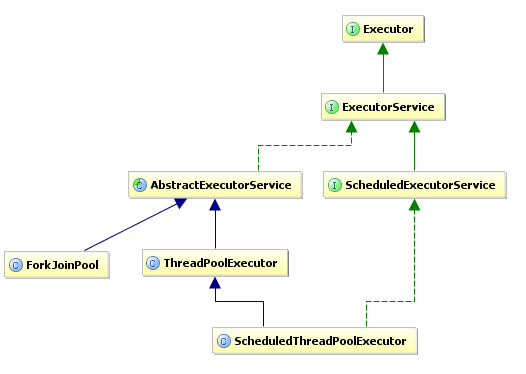

Executors Framework

- Executor framework provides a standard means of decoupling ‘task submission’ and ‘task execution’

- Independent Task - task that doesn’t depend on the state/result of other tasks

- Only independent tasks should be submitted to executors/thread pool. Otherwise leads to starvation deadlock

Disadvantages of unbounded thread creation

- Overhead involved in thread creation and teardown

- Resource consumption - threads consume memory and adds pressure to GC

- Stability - there is a limit on how many threads could be created. Breaching that will crash the program.

Task Execution Policy

- number of threads -> single/multi-threaded

- queue -> bounded/unbounded queue

- order of execution -> FIFO, LIFO, priority order

Task Types

Runnable&Callable- represent abstract computation tasks. Runnable neither returns results nor throws exceptionFuture- represents lifecycle of a task and provides methods to test whether the task completed/cancelled/result available.- Future.get() call blocks until the result is available

- Instead of polling on Futures, use

CompletionService

- Periodic tasks

Timer- supports only absolute timing- If a recurring TimerTask is scheduled to run every 10 ms and another TimerTask takes 40 ms to run, the recurring task either (depending on whether it was scheduled at fixed rate or fixed delay) gets called four times in rapid succession after the long-running task completes, or “misses” four invocations completely. Scheduled thread pools address this limitation by letting you provide multiple threads for executing deferred and periodic tasks.

- Timer thread doesn’t catch the exception, so an unchecked exception thrown from a TimerTask terminates the timer thread.

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor- supports only relative timing. Always prefer this over Timer.

Class diagram

ExecutorInterface- has only one method -

execute(Runnable) - useful tool to solve producer-consumer type problems

- Executors decouple task execution & task submission

- has only one method -

ExecutorServiceinterface- extends Executor interface

- provides additional methods to shutdown executor either forcefully/gracefully

Concurrent Data Structures

Blocking Data Structures

- Blocking Queue - used in producer-consumer problems.

- Bounded Queue - blocks read when empty and blocks write when full

- Unbounded Queue - blocks read when empty and never full

- ArrayBlockingQueue - FIFO

- LinkedBlockingQueue - FIFO

- PriorityBlockingQueue - Priority-ordered

- SynchronousQueue - No storage space (size=0). Producer blocks until consumer is available.

- Semaphore

- Blocking Deque (double-ended queue)

- Deque & Blocking Deque are good for “work stealing pattern” which is better than producer-consumer pattern.

Synchronizers

Synchronizer is any object that keeps the shared mutable data consistent. We don’t need them if we can make data immutable or unshared.

Note: Blocking Queue is both collection and a synchronizer

1) FutureTask

- represents asynchronous tasks (implement Future)

- acts like a latch.

- Future.get()

- if complete, returns computation result

- if not, blocks until result is available or an exception is thrown

2) Sempahore

- Semaphores are often used to restrict the number of threads than can access some (physical or logical) resource.

- Counting semaphores control the number of activities that can access a certain resource or perform a given action at the same time.

- semaphores manage a set of virtual permits

- activities acquire permit and release them

- if no permit available, acquire blocks

- semaphore with 1 permit acts as a mutex

- can be used to convert any collection into a ‘blocking bounded collection’

- semaphore does not associate permits with threads. So a permit acquired in one thread can be release from another thread.

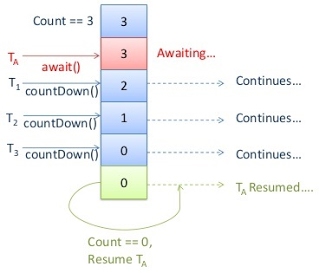

3) Latches

- acts as a gate:

- initially when the gate is closed, no threads can pass.

- gate opens after the terminal state is reached and all threads pass.

- once open the gate never closes

- any thread is allowed to call countDown() as many times as they like. Coordinating thread which called await() is blocked until the count reaches zero.

Limitations

- A latch cannot be reused after reaching the final count

- number of participating threads should be specified at creation time and cannot be changed.

- In the picture, Thread TA waits until all the 3 threads (1-3) complete.

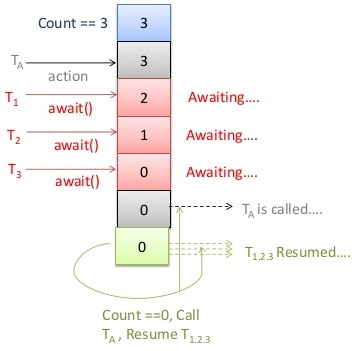

4) Barriers

CyclicBarrierlets a group of threads wait for each other to reach a common barrier point.- It also allows you to get the number of clients waiting at the barrier and the number required to trigger the barrier. Once triggered the barrier is reset and can be used again.

- Unlike CountdownLatch, barrier can be reused by calling reset() (hence the name cyclic).

CyclicBarriercan be provided an optional Runnable to execute after reaching the barrier point.- Useful in loop/phased computations where a set of threads need to synchronize before starting the next iteration/phase.

CyclicBarrier- if a thread has a problem (timeout, interrupted…), all the others that have reached await() get an exception. The CyclicBarrier uses an all-or-none breakage model for failed synchronization attempts: If a thread leaves a barrier point prematurely because of interruption, failure, or timeout, all other threads waiting at that barrier point will also leave abnormally via BrokenBarrierException (or InterruptedException if they too were interrupted at about the same time).

Limitations

- number of participating threads should be specified at creation time and cannot be changed.

5) Exchanger

An Exchanger lets a pair of threads exchange objects at a synchronization point.

6) Phaser (1.7)

- A flexible synchronizer to do latch and barrier semantics

- with less code and better interrupt management

- only synchronizer in Java that is compatible with fork/join framework

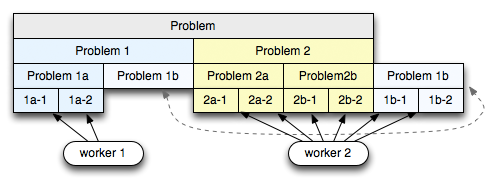

7) ForkJoinPool (1.7)

ForkJoinPool: An instance of this class is used to run all your fork-join tasks in the whole program.RecursiveTask<V>: You run a subclass of this in a pool and have it return a resultRecursiveAction: just likeRecursiveTaskexcept it does not return a result-

ForkJoinTask<V>: superclass ofRecursiveTask<V>andRecursiveAction.forkandjoinare methods defined in this class. You won’t use this class directly, but it is the class with most of the useful javadoc documentation, in case you want to learn about additional methods. -

Example

- In the example below, given an array and a range of that array. The

computemethod sums the elements in that range. - If the range has fewer than

SEQUENTIAL_THRESHOLDelements, it uses a simple for-loop like you learned in introductory programming. - Otherwise, it creates two

Sumobjects for problems of half the size. It uses fork to compute the left half in parallel with computing the right half, which this object does itself by callingright.compute(). To get the answer for the left, it callsleft.join(). - Why do we have a

SEQUENTIAL_THRESHOLD? If we create aSumobject for every number, then this creates a lot moreSumobjects and calls tofork, so it will end up being much less efficient despite the same asymptotic complexity. - Why do we create more Sum objects than we are likely to have procesors? Because it is the framework’s job to make a reasonable number of parallel tasks execute efficiently and to schedule them in a good way. By having lots of fairly small parallel tasks it can do a better job, especially if the number of processors available to your program changes during execution (e.g., because the operating system is also running other programs) or the tasks end up taking different amounts of time.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | |

Work-Stealing Technique

- Fork-join is based on Work-Stealing technique for parallel exuection

- One of the key challenges in parallelizing any type of workload is the partitioning step: ideally we want to partition the work such that every piece will take the exact same amount of time. In reality, we often have to guess at what the partition should be, which means that some parts of the problem will take longer, either because of the inefficient partitioning scheme, or due to some other, unanticipated reasons (e.g. external service, slow disk access, etc).

-

This is where work-stealing comes in. If some of the CPU cores finish their jobs early, then we want them to help to finish the problem. However, now we have to be careful: trying to “steal” work from another worker will require synchronization, which will slowdown the processing. Hence, we want work-stealing, but with minimal synchronization.

- Fork-Join solves this problem in a clever way using: recursive job partitioning and a double-ended queue (deque) for holding the tasks.

- Given a problem, we divide the problem into N large pieces, and hand each piece to one of the workers (2 in the diagram here). Each worker then recursively subdivides the first problem at the head of the deque and appends the split tasks to the head of the same deque. After a few iterations we will end up with some number of smaller tasks at the front of the deque, and a few larger and yet to be partitioned tasks on end.

-

Imagine the second worker has finished all of its work, while the first worker is busy. To minimize synchronization the second worker grabs a job from the end of the deque (hence the reason for efficient head and tail access). By doing so, it will get the largest available block of work, allowing it to minimize the number of times it has to interact with the other worker (aka, minimize synchronization). Simple, but a very clever technique!

- Map-Reduce and Fork-Join - “map-reduce” workflow is simply a special case of this pattern. Instead of recursively partitioning the problem, the map-reduce algorithm will subdivide the problem upfront. This, in turn, means that in the case of an unbalanced workload we are likely to steal finer-grained tasks, which will also lead to more need for synchronization - if you can partition the problem recursively, do so!

8) StampedLock (1.8)

Phaser and StampedLock Concurrency Synchronizers (Heinz Kabutz)

Java Memory Model

….

Concurrency Programming Models

- Actor Model

- STM model

Concurrency Frameworks

LMAX Disruptor - High Performance Inter-Thread Messaging Library. Excellent blog on this topic : http://mechanitis.blogspot.com/2011_07_01_archive.html

FAQs

- how to test throughput of concurrent programs?

- Work stealing pattern - learn

- Java 1.5 Double-checked locking mechanism

- What is the significance of Stack Size in a thread? (JVM Option -Xss)

- Difference between sleep(), yield(), and wait()

sleep(n)says “I’m done with my time slice, and please don’t give me another one for at least n milliseconds.” The OS doesn’t even try to schedule the sleeping thread until requested time has passed.yield()says “I’m done with my time slice, but I still have work to do.” The OS is free to immediately give the thread another time slice, or to give some other thread or process the CPU the yielding thread just gave up.wait()says “I’m done with my time slice. Don’t give me another time slice until someone calls notify().” As with sleep(), the OS won’t even try to schedule your task unless someone calls notify() (or one of a few other wake up scenarios occurs).

- THOU SHALT NOT

- call

Thread.stop()- All monitors unlocked by ThreadDeath - call

Thread.suspend()orThread.resume()- Can lead to deadlock - call

Thread.destroy()- Not implemented (or safe) - call

Thread.run()- Wonʼt start Thread! Still in caller Thread. - use ThreadGroups - Use a ThreadPoolExecutor instead.

- call

- How to analyze Java Thread dumps

- Tools to detect deadlocks?

Bibliography

- Books

- Java Concurrency in Practice

- The CERT Oracle Secure Coding Standard for Java

- Blogs & Articles

- Oracle’s Multithreaded Programming Guide - concepts and terminologies

- Alex Miller’s Concurrency Gotchas - http://www.slideshare.net/alexmiller/java-concurrency-gotchas-3666977

- http://www.slideshare.net/nadeembtech/java-concurrecny

- http://www-128.ibm.com/developerworks/library/j-csp1.html

- http://www-128.ibm.com/developerworks/library/j-csp2.html

- http://www-128.ibm.com/developerworks/library/j-csp3.html

- http://www.javaworld.com/javaworld/jw-10-1998/jw-10-toolbox_p.html

- http://www.baptiste-wicht.com/series/java-concurrency-tutorial/

- http://www.slideshare.net/sjlee0/robust-and-scalable-concurrent-programming-lesson-from-the-trenches

- http://www.slideshare.net/choksheak/advanced-introduction-to-java-multi-threading-full-chok

- http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/j-jtp08223/

- DZone RefCard - Java Concurrency