VCS

Overview

- Difference between VCS and DVCS.

- What is the advantage of having a distributed VCS?

- no single point of failure in the event of a crash or corruption

- Principles and best practices when it comes to branching

Git

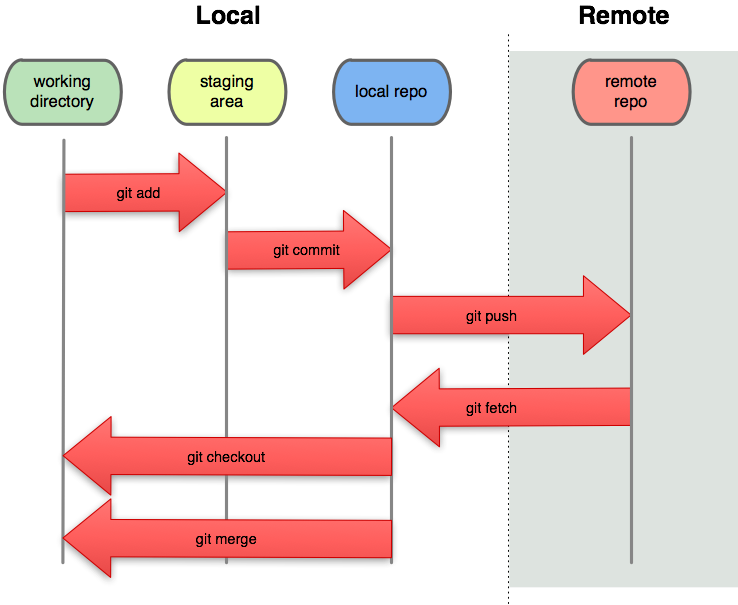

How Git works?

Workflow models

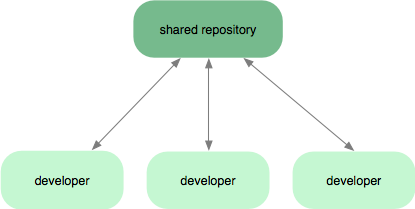

- SVN-style centralized workflow

- A very common Git workflow, especially from people transitioning from a centralized system. Git will not allow you to push if someone has pushed since the last time you fetched, so a centralized model where all developers push to the same server works just fine.

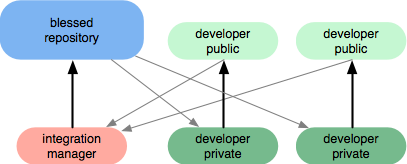

- Integration Workflow / The open-source Workflow / Fork & Pull Requests

- a single person who commits to the ‘blessed’ repository, and then a number of developers who clone from that repository, push to their own independent repositories and ask the integrator to pull in their changes. This is the type of development model you often see with open source or GitHub repositories.

- Dictator and Lieutenants Workflow

- For more massive projects, you can setup your developers similar to the way the Linux kernel is run, where people are in charge of a specific subsystem of the project (‘lieutenants’) and merge in all changes that have to do with that subsystem. Then another integrator (the ‘dictator’) can pull changes from only his/her lieutenants and push those to the ‘blessed’ repository that everyone then clones from again.

| Centralized workflow | Integration Workflow |

|---|---|

|

|

Advantages

- Distributed, not centralized:

- With Git, you have a local copy/clone of the entire repository which could be used offline. Due to this, there is no single point of failure in case of a crash or corruption. Every developer has his own copy of the repository.

- Smaller & Faster - To save space and transfer time, the data is stored after applying compression.

- Branching and merging is easier

- Atomic transactions: Like SVN, transactions are atomic - ensures that the version control database is not left in a partially changed or corrupted state while an update or commit of number of unrelated changes is happening.

- Content-Addressable file store - SHA1 hash value is generated out of the file contents to identify a file.

Basic concepts

- Checkout vs clone, Commit Vs Push

- Branching vs Forking

- Branches are light-weight and merging is easy.

- In SVN, each file & folder can come from a different revision or branch. This leads to confusion in case of a failure.

- Workflows

- Unlike other VCS systems, Git does not impose any particular workflow.

- Well-suited for open source community development.

- Git-SVN Bridge - The central repository is a Subversion repo, but developers locally work with Git and the bridge then pushes their changes to SVN.

- Unlike SVN which creates .svn directories in every single folder, Git only creates a single .git folder.

- Sparse checkouts.

- Git tracks content rather than file - renaming a file, moving it to a different location

- version control outside of source code

https://git.wiki.kernel.org/index.php/GitSvnComparsion

Concepts

HEAD In Git,the HEAD points to the latest commit in a branch

Base Commit In Git, the last common commit between two branches is called ‘base commit’

Conflicts When Git merges the two branches, it looks at the changes in each branch since the base commit. When there are unambiguous differences—like changes to different files, and sometimes different parts of the same file—the changes are applied. However, if there are changes to the same parts of the same file, and Git can’t determine which changes to keep, it raises a conflict.

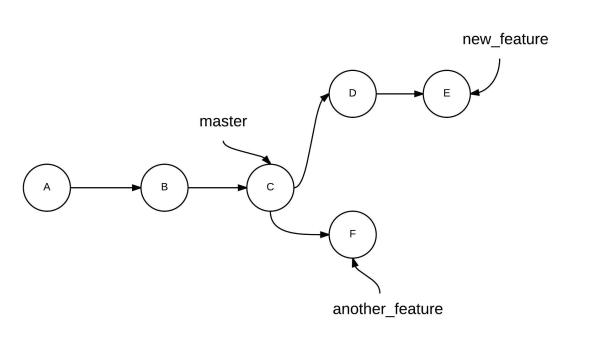

Branching

When we merge branches and there are no conflicts, such as above, only the branch pathway is changed and the HEAD of the branch is updated. This is called the fast forward type of merge.

1 2 | |

The alternate way of merging branches is the no fast forward merge, by postfixing --no-ff to the merge command. In this way, a new commit is created on the base branch with the changes from the other branch.

1

| |

Git Command Reference

gitk- build-in git GUIgit addgit add <file_name>- tells Git start tracking a new file or it could mean to stage the changes in an existing filegit add .- tells Git to start tracking current directory and sub-directoriesgit ls-files --deleted | xargs git rm- stage locally deleted files for committing

git bisect- performs a binary search through commitsgit blame <file_name>- gives detailed information about each line in the file.git branchgit branch- lists only local branch namesgit branch -a- lists all branch names, both local and remotegit branch -r- lists only remote branch namesgit branch <branch_name>- Creates a branch off of latest commit, but doesn’t switch the local to itgit branch -b <branch_name>- Creates a branch off of latest commit and switches to itgit branch -b <branch_name> <commit_id>- Creates a branch off of given commit idgit branch -m <branch_name>- Rename current branchgit branch -D <branch_name>- deletes the branch without warning of any uncommitted filesgit branch -d <branch_name>- deletes the branch with warning of any uncommitted files. To delete the remote branch,git push <remote_name> <branch_name>

git checkoutgit checkout- change the status of files to a different branchgit checkout <filename>- revert the given file to the state during the last commit.git checkout -b <branch_name>- create a new branch named and switch to itgit checkout -b <branch_name> upstream/<branch_name>- create a new branch <branch_name> and associates it withupstream/branch_name.git checkout <branch_name>- switch to a given branchgit checkout -- takes back to the previous branch (likecd -)git checkout -- <filename>- replace changes in your working tree with the latest content in HEADgit checkout -b <branch_name> <tag_name>- create a branch locally and checkout to a given tag

git clone- If you clone a repository, the source from which you cloned from is designated as the

originremote by default. You may modify the remote using the git remote command.

- If you clone a repository, the source from which you cloned from is designated as the

git commitgit commit --amend -m 'new message'- change the commit message of the last commit

git configgit config --list --show-origin- lists configurations and their origin files

git describegit describe --tags --abbrev=0git describe --tags --abbrev=0 --match="beta2_ddl_*"

git diffgit diff <source_branch> <target_branch>

git fetchgit fetch- updates the branches of the local repository from the remote origin. Fast-forwarding by defaultgit fetch <remote_name>- updates the branches of the local repository from remote. (Following a fetch, to update your local branch you need to merge it with appropriate branch from the remote. E.g.,git merge <remote_name>/<branch_name>)git fetch upstream refs/pull/<pull#>head:pull_<pull#>- https://coderwall.com/p/z5rkga/github-checkout-a-pull-request-as-a-branch

git fsckgit fsck --lost-found- search for commits that aren’t part of any branch

git loggit loggit log -n 2orgit log -2- view last 2 commits onlygit log --all- view commits in all branchesgit log --all --decorate --oneline- decorate and one liner logsgit log --all --decorate --oneline --graph- graphical viewgit log --tags --simplify-by-decoration --pretty="format:%ci %d" -n5- displays the last 5 tags createdgit log --after='2015-3-1' --before='2015-5-1'git log --follow <file_name>- trace changes in a single file.blameenables you to check only the current contents of a file. Thelog --followcommand, on the other hand, lists the changes the file has gone through since Git started tracking the file.git log --author='fizal'git log --grep='search_text'- search commit messages

git mergegit merge <remote_name>/<branch_name>- Following a fetch, to update your local branch you need to merge it with appropriate branch from the remote. This is basically merging the branch <remote_name>/<branch_name> with your current active branch.git merge --abort- after initiating a merge that’s resulted in conflicts, if you’re overwhelmed and want to go back to the pre-merge stategit merge --rebase master

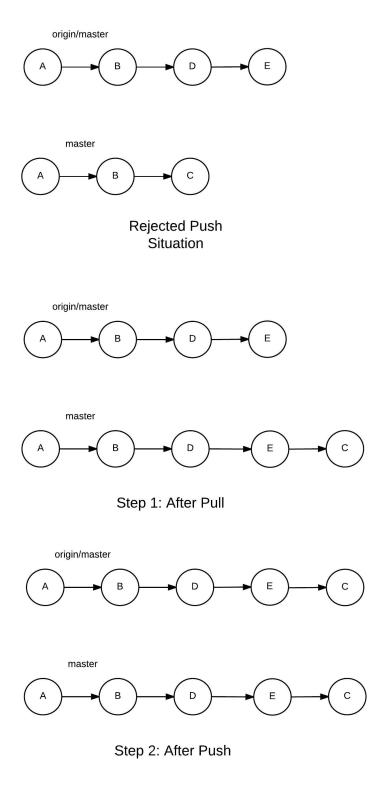

git pushgit push- pushes the code in the current branch to the

originremote branch of the same name. - A branch is created if the branch with the same name as the current local branch doesn’t exist on the origin.

- Push is rejected with an error it is non-fast-forward if the remote branch has been updated since your last synchronization.

- pushes the code in the current branch to the

git push <remote_branch>- pushes the code in the current branch to the remote_branch. A branch is created if the branch with the same name as the current local branch doesn’t exist on the remote.git push <remote_name> <branch_name>- remote_name is origin/upstreamgit push -f origin <branch_name>- forcefully pushes. Typically you need this after changes like squashgit push <remote_name> --tags- push by default doesn’t push the tags to the remote. Adding--tagsdoes that.git push <remote_name> <tag_name>- to specifically push a tag to a remote

git pullgit pull=git fetch + git merge. Downloads the code from the master branch of the origin remote branch and then merges the code with the current active branch. Pulls are fast-forwarding by default.git pull <remote_name> <branch_name>-git pull --rebase <remote_name> <branch_name>

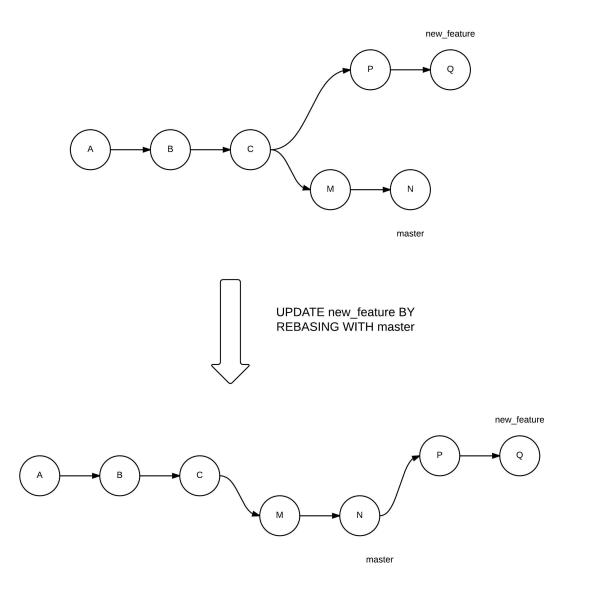

git rebase- merging mechanism that avoids loops in the project history.git rebase -i- lists down all the local commits and gives you the option to pick/reword/edit/squash/fixup/exec/drop a commitgit rebase master- If you’re rebasing a master into new_feature, the new commits in master are put before the new commits in new_feature that are not common to master. Run this command from new_feature branch.git rebase --abort

git reflog- log of refs- A ref, short for a reference, is a way of referencing a commit. In other words, the hash is a name, whereas a ref is a pointer.

- Special refs -

HEAD,ORIG_HEAD,MERGE_HEAD,FETCH_HEAD - The reflog command stores the records for each action you perform in your repository. When you push the changes, this data isn’t synced with the server. Using the reflog command is necessary if you want to review changes to your local repository. It could also be used to recover lost commits.

- If you make a hard reset and lose a commit or two, you can safely go back to any commit you made earlier. For instance, you can run the reflog command, which would have a record corresponding to the time when the commit was created, mentioning the commit hash. When you know the hash, you can start a new branch based on that commit to go back to the state of that commit.

git reflog expire --expire=never- The reflog command only tracks back changes for a certain amount of time. Git is responsible for cleaning up the reflog data periodically, which by default is 90 days. This command sets the reflog to never expire.

git remotegit remote -v- List the current configured remote repository for your fork.git remote add upstream- https://help.github.com/articles/configuring-a-remote-for-a-fork/

- http://www.eqqon.com/index.php/Collaborative_Github_Workflow

- http://blog.scottlowe.org/2015/01/27/using-fork-branch-git-workflow/

git resetgit reset HEAD <file_name>- unstage changes and reset a file to the state where the HEAD points togit reset --soft HEAD~1- to rollback a commitgit reset --hard <remote_name>/<branch_name>- Throws away local changes and makes the working tree and index same as the remote version

git rev-parse HEADgit rmgit rm --cached <file_name>- untracks a file without deleting from local file systemgit rm --cached -f <file_name>- untracks a file and forcefully deletes from local file system

git shortlog- shows the authors who have contributed to the repository and their commitsgit showgit show <commit_id>- shows information about a commit. Even partial commit ids are acceptedgit show 'git describe' --pretty=fuller

git stashgit stash- to stash uncommitted changesgit stash list- list out the stashes in the local repositorygit stash apply- to apply the changes that were stored in the last stashgit stash apply stash@{1}- to restore an old stash

git statusgit taggit tag- lists all the tags. There are two types of tags—lightweight and annotated. Lightweight tags contain only the tag name and point to a commit. Annotated tags contain the tag name, information about the tagger, and a message associated with the tag.git tag <tag_name>- create lightweight tag associated with the latest commitgit tag -a <tag_name> -m <commit_message>- create annotated taggit tag 1.0.0 1b2e1d63ff- the 1b2e1d63ff stands for the first 10 characters of the commit id you want to reference with your tag

Frequent actions

Undo tracking operation

Below command asks Git to untrack the file, but let it remain in the file system. Same command can be used to remove a file from the repository, but a commit is needed after this to take effect.

1

| |

Undo stage operation

You make changes to a tracked file and then run git add to stage it for commit. To unstage the changes, run below command to reset a file to the state where the HEAD or the last commit points to.

1

| |

Revert back to an older commit To revert back local changes and go back to the state during the last commit.

1

| |

Undo commit operation

To rollback a commit. The --soft option undoes a commit, but lets the changes you made in that commit remain staged for you to review. The HEAD~1 means that you want to go back one commit from where your current HEAD points.

1

| |

The process of committing involves three steps: * making changes in a file, * staging it for a commit, and * performing a commit operation.

- The

--softoption takes us back to just before the commit, when the changes are staged. - The

--mixedoption takes us back to just before the staging of the files, where the files have just been changed. - The

--hardoption takes us to a state even before you changed the files.

The reset command changes the history of the project, but revert undoes the changes made by the faulty commit by creating a new commit that reverses the changes.

Undo push operation

To revert the changes pushed to the central repository

1 2 | |

However, if you also want the other commit(s) to vanish from the remote repository, you first need to go for a reset command—deleting the unwanted commit—and then push the changes to the remote. If you perform a normal git push, the push will be rejected—because the origin HEAD is at a more advanced position than your local branch. Therefore, you need to force the change with a postfix, -f, which forces the push on the remote origin:

1 2 | |

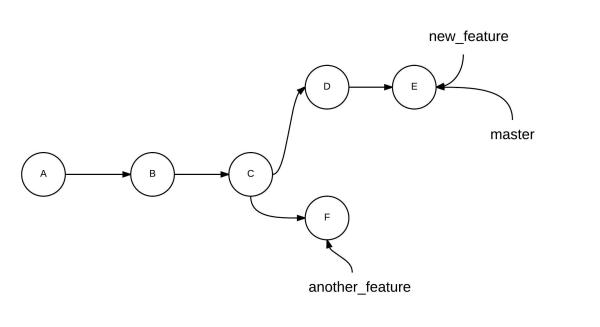

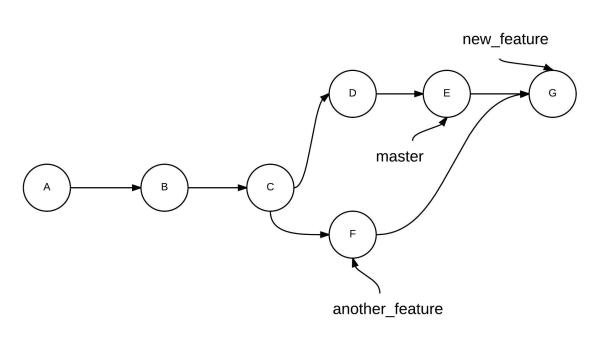

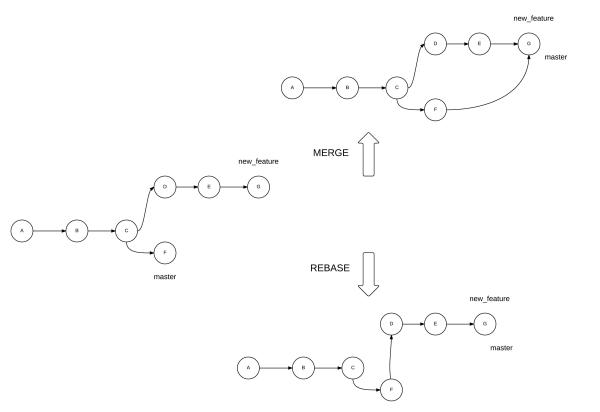

Merging Branches

To merge branch new_feature with branch master

|

|

1 2 | |

To merge branch another_feature with branch new_feature

1 2 | |

| Merge | Rebase |

|

|

Hard fetch

To drop all your local changes and commits, fetch the latest history from the server and point your local master branch at it like this

1 2 | |

Rebase

git rebase master - If you’re rebasing a master into new_feature, the new commits in master are put before the new commits in new_feature that are not common to master. To do so, run the following command from the new_feature branch

git merge --rebase master - If you’re working in a team, you should first checkout to master, pull from the upstream branch to update your master with the latest commits, and then switch back to new_feature before running the above command.

git pull --rebase origin master - When you’re pulling changes, you can use rebase too. It essentially puts the new commits in the master of the remote in your history, and then superimposes your commits on them.

git rebase -i or git rebase --interactive

A squash operation changes the history of your branch. If you need to push your changes after a squash operation, you need to use the -f option, or your push will be rejected.

When you have multiple commits in your PR, run rebase so that the change is merged as a single commit.

Here are the steps to do it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

To cancel a rebase in progress before pushing: git rebase abort

Cherry picking

create a branch based off of a commit

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Diff

- Show unpushed commits:

git log origin/develop..HEAD - To list the files modified between ‘origin/develop’ and my current branch:

git log --stat origin/develop..HEAD - To list the files modified between 2 branches:

git log --stat origin/develop..origin/feature/JIRA-123

Advanced Concepts

Content-Addressable Names

The Git object store is organized and implemented as a content-addressable storage system. Specifically, each object in the object store has a unique name produced by applying SHA1 to the contents of the object, yielding an SHA1 hash value. Because the complete contents of an object contribute to the hash value and the hash value is believed to be effectively unique to that particular content, the SHA1 hash is a sufficient index or name for that object in the object database. Any tiny change to a file causes the SHA1 hash to change, causing the new version of the file to be indexed separately. SHA1 values are 160-bit values that are usually represented as a 40-digit hexadecimal number, such as 9da581d910c9c4ac93557ca4859e767f5caf5169. Sometimes, during display, SHA1 values are abbreviated to a smaller, unique prefix. Git users speak of SHA1, hash code, and sometimes object ID interchangeably.

An important characteristic of the SHA1 hash computation is that it always computes the same ID for identical content, regardless of where that content is. In other words, the same file content in different directories and even on different machines yields the exact same SHA1 hash ID. Thus, the SHA1 hash ID of a file is an effective globally unique identifier. A powerful corollary is that files or blobs of arbitrary size can be compared for equality across the Internet by merely comparing their SHA1 identifiers.

Pack files

Efficient file storage mechanism. If you were to just change or add one line to a file, Git might store the complete, newer version and then take note of the one line change as a delta and store that in the pack too.

The main points I like about DVCS are those :

You can commit broken things. It doesn’t matter because other peoples won’t see them until you publish. Publish time is different of commit time.

Because of this you can commit more often.

You can merge complete functionality. This functionality will have its own branch. All commits of this branch will be related to this functionality. You can do it with a CVCS however with DVCS its the default.

You can search your history (find when a function changed )

You can undo a pull if someone screw up the main repository, you don’t need to fix the errors. Just clear the merge.

When you need a source control in any directory do : git init . and you can commit, undoing changes, etc…

It’s fast (even on Windows )