Operations

Book: Beyond Blame by Dave Zwieback

- Prof. Erik Hollnagel: “E.T.T.O. is efficiency-thoroughness trade-off. You can’t have both efficiency and thoroughness, and that we have to continually balance between the two.”

- Hindsight bias

- We make decisions in real time, but evaluate them with the benefit of hindsight. Whether a decision (like a particular trade-off) was correct can be determined only in retrospect.

- Hindsight bias or colloquially “hindsight 20/20”.

- Daniel Kahneman—one of the people who’s been studying cognitive biases since the seventies—says that it’s easier to spot biases in others than in ourselves.

- Counterfactuals

- “Anytime you hear ‘didn’t,’ ‘could have,’ ‘if only,’ or ‘should have,’ you can be pretty sure that whoever is saying them is under the influence of hindsight bias. These phrases are called ‘counterfactuals’.

- Wishful thinking: ‘Mike could have asked for help,’ or ‘Mike should have done more testing in the lab,’ or ‘Mike didn’t do the right thing,’ are all counterfactuals, and are all evidence of hindsight bias.

- Outcome bias

- With outcome bias, we judge the quality of decisions made in the past given the outcome, which, of course, is unknown at decision time. Outcome bias is almost always there when we experience hindsight bias.

- The flip side of outcome bias is that it can lead us to hero worship — celebrating people who made pretty bad or risky decisions that somehow still turned out all right.

- The ends, after all, justify the means—unless you get caught.

- Fundamental attribution error bias

- if I were under the influence of fundamental attribution error, I would think of this grumpiness as part of your personality, instead of attributing it to a lack of caffeine in your system

- Black swan event hiding in the system, waiting for just the right set of conditions to manifest.

- It stops us from learning about the deeper underlying conditions for outages, or even what’s needed to make things work.

- Blame is the frigid, arctic air that stunts the development of a deeper understanding of our systems, which is the only way we can really improve them.”

- Being accountable is being beyond blame. Being accountable is accepting responsibility for our actions, and providing the full account, without accepting the blame. So we can learn. And only through this learning can we make our organization more resilient to failures that will inevitably happen.

- We talk a lot about making the firm a ‘learning organization’—well, here’s a very concrete step we can take to maximize learning. We want our employees to innovate? Being able to fail in a safe way and learn from it will encourage more innovation. Or we can continue on our current path, and effectively encourage our employees to find innovative ways to limit their personal exposure and liability. Or find employment elsewhere.”

- Remind everyone that the point is not to judge, reprimand, or punish, but to understand and learn from what happened.

Cynefin Framework

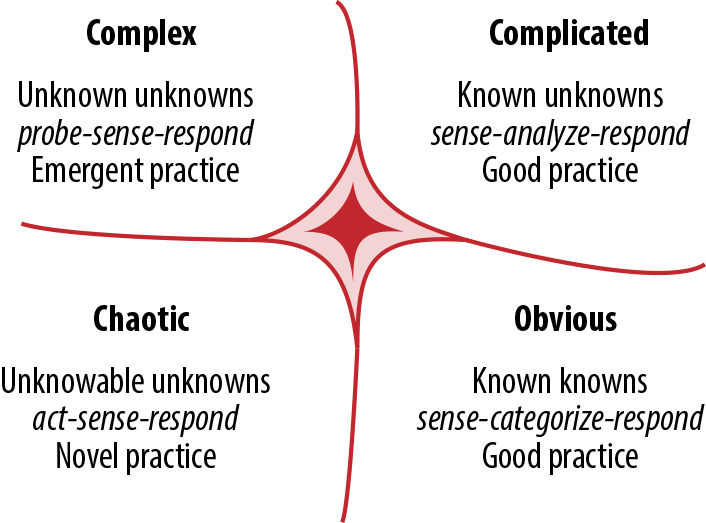

- Harvard Business Review article from 2007 by David Snowden and Mary Boone introduced a complexity framework called ‘Cynefin.’ It’s a way of thinking about complexity. And this framework is not just philosophy—it’s based on complexity science, and it’s practical, it’s usable.”

- This is a framework that buckets systems into one of the five domains: obvious, complicated, complex, chaotic, and, finally, unknown.

- Obvious: Imagine a fast-food chain restaurant. No room for creativity here, just follow the process.

- Complicated:

- In a fancy, five-star restaurant, there’s a lot more creativity and a lot more experience required. You still have a recipe to follow—what you might call a ‘good practice’—but you need a whole lot more experience in order to operate here, especially when things go wrong. That’s why this one is called the ‘domain of experts’.

- Also, complicated systems are far less constrained than obvious ones, but both are still within the realm of ordered domains.”

- Complex:

- Imagine a cooking competition show. These experiments are safe-to-fail experiments. They won’t die, even if they get eliminated from the competition. But no one knows in advance who’s going to win, and previous experience is not that valuable here.

- Chaotic:

- Imagine unleashing a gang of toddlers into the kitchen. No constraints. They’re running around with knives, throwing things around, locking one another in freezers, and of course, playing with gas stoves.

- These chaotic systems are, luckily, very short lived. Someone usually steps in and sets some constraints, moving the system into a more ordered domain.

- In both the complex and the chaotic domains, there’s no best practice—not even good practice. We can’t predict how things will go in advance, and we might not even be able to establish causality in retrospect. The point is, we have to act differently than we do in the more ordered domains, if we find ourselves working within these unordered ones.

- Unknown

- We’re mostly in the complicated or complex domains. And when we have outages, almost certainly in the complex or chaotic ones.

- Assuming you’re working within a complex system is probably a safe default. Most of the time we don’t know how our systems are working, and whether the changes we’re making will work or backfire. But we can experiment in safe-to-fail ways, and find out more about the constraints of our systems. We can develop heuristics about how to act within them. And, with some luck, we can move these systems into the more predictable and ordered domains by adjusting the constraints. This is something that humans are quite good at.

Learning Review Framework

Fundamentally, in a learning review,

- we recognize that we’re most likely working with a complex system, which requires a different approach than working with other types of systems.

- We know that in complex systems, the relationship between causes and effects can be teased out only in retrospect, if ever.

- We’re also not looking for a single root cause. Instead, we hope to understand the multitude of conditions, some of which might be outside our control.

- We also accept that some of the conditions will remain unknown and unknowable.

In the learning-review framework, if we ever get to a single root cause—especially if it’s a person—we know we’re not digging deep enough.

Let’s remember that the single root cause of all functioning and malfunctioning systems is impermanence. If you’ve got to blame something, blame impermanence.

Anything disclosed during a learning review as protected information—meaning it won’t be used against the people who share it.

- First of all, and perhaps most importantly, starting now we will guarantee that no one providing a full account of their actions during incidents will be penalized in any way.

-

The information that you provide during postmortems cannot and will not be used against you—not as a reason for demotion, or reduced compensation, or any other disciplinary action.

- 1) Set the context.

- The purpose of the learning review is to learn so that we can improve our systems and organizations. No one will be blamed, shamed, demoted, fired, or punished in any way for providing a full account of what happened. Going beyond blame and punishment is the only way to gather full accounts of what happened—to fully hold people accountable.

- We’re likely working within complex, adaptive systems, and thus cannot apply the simplistic, linear, cause-and-effect models to investigating trouble within such systems.

- Failure is a normal part of the functioning of complex systems. All systems fail — it’s just a matter of time.

- We seek not only to understand the few things that go wrong, but also the many things that go right, in order to make our systems more resilient.

- The root cause for both the functioning and malfunctions in all complex systems is impermanence (i.e., the fact that all systems are changeable by nature). Knowing the root cause, we no longer seek it, and instead look for the many conditions that allowed a particular situation to manifest. We accept that not all conditions are knowable or fixable.

- Human error is a symptom — never the cause — of trouble deeper within the system (e.g., the organization). We accept that no person wants to do a bad job, and we reject the “few bad apples” theory. We seek to understand why it made sense for people to do what they did, given the information they had at the time.

- While conducting the learning review, we will fall under the influence of cognitive biases. The most common ones are hindsight, outcome, and availability biases; and fundamental attribution error. We may not notice that we’re under the influence, so we request help from participants in becoming aware of biases during the review. (Read Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.)

- 2) Build a timeline.

- a) We want to understand what happened from the perspective of the individuals involved: what did they know, when, and how did it make sense?

- b) Describe what happened; don’t explain.

- c) The more diverse points of view that you can collect, the fuller the picture of the incident. Encourage and note divergent and dissenting opinions.

- d) As the facilitator, your job is to listen to discover and verify by synthesizing.

- 3) Determine and prioritize remediation items, if any. This can be done separately from building a timeline.

- 4) Publish the learning review write-up as widely as possible.

- If the incident negatively impacted people, consider using the Three Rs (“Regret, Reason, Remedy,” from Drop the Pink Elephant by Bill McFarlan) to structure the write-up.

- During the learning review, listen for, and help participants be aware of blaming, cognitive biases, and counterfactuals (“We could have/we should have/if only we/we didn’t”). Use empathy and humor throughout the learning review to defuse tense situations, especially at the beginning. Ask lots of questions, including these:

- Did we know this at the time or is it obvious only in hindsight?

- When did we learn this fact?

- How does knowing the outcome affect our perception of the situation (or the people involved in the incident)?

- Is this a likely explanation because we’ve recently had a similar problem? How is this situation different?

- Can you please describe what happened without explaining (too much)?

- Any one of us would have done what Bob or Sue did. Let’s focus on how it made sense at the time, and what we can do better in the future.

- This sounds like a counterfactual. What actually happened, what did we know, and how did it make sense at the time?

- How do we know this?